Korea began to decorate its white porcelain in blue by the early 15th century; a century later than China and two centuries earlier than Japan. During that early Joseon period, Korea had about four hundred kilns in operation to produce quality white porcelain, which the Chinese court often requested as diplomatic tribute and trade. With the infrastructure and quality, the Joseon dynasty could have emerged as one of the world’s two pioneering blue and white porcelain manufacturers along with China. Instead, the dynasty sustained its preference for pure white porcelain. Furthermore, it classified blue and white as an unnecessary luxury and eventually issued an ordinance to ban its production other than for the royal household needs. The ban remained in effect until the end of the 18th century.

Many rationales were behind the deterrent policy of the Joseon dynasty, including its founding ideology, Neo Confucianism. In Confucian society, where the virtues of modesty and humility were highly esteemed, the exuberant blue and white looked excessive and immoderate. In addition, the unstable supply chain caused by a series of wars with Japan and China and the prohibitively expensive cost of the cobalt blue pigment of West Asia, which had been imported via China at that time, further discouraged the dynasty’s incentives for blue and white production.

Interestingly, Korean blue and white developed into something unique and distinctive from other blue and white produced elsewhere under these adverse economic, political, and social circumstances. Korean blue and white can be divided into four categories, which loosely coincide with its development phases, spanning from the early 15th century to the late 19th century.

Dragon Jar as the Ultimate Symbol of Royalty

In Korea, dragon jars functioned as essential mood enhancers at royal events, such as ancestral rites, coronation ceremonies, and royal banquets. Prominently mounted on a tall stand in the venue, they were to send out an immediate visual message that the event to be held would be solemnly important. Few dragon jars of the early Joseon period exist today. However, some drawings in Sejong Silrok Oryeui (the Books of Protocol and Etiquette) [1] suggest that they were similar to the jun-type jar of Ming China, on which dragons are most characteristically depicted with three claws.

Sold for $3,437

Korean-style dragon jars emerged during the mid-18th century when the Joseon court needed to restore the royal supremacy defiled by a series of prolonged wars. They are generally tall, up to 18 inches, and have a voluminous shoulder that curves down to form a relatively small waist and base in proportion. The necks are short, about an inch or so, and slightly widen upward to make the mouth rim more or less equal to the base in diameter. The the dragon is usually characterized by a face speckled with variously sized dots, a sinuous neck and chest protruding enough to form a bigger S-curve with the head, and primarily four-clawed feet.

This mid-period style transformed during the 19th century, when the popularity of the dragon motif became widespread even among the ordinary people and dragon jars were produced on private commissions not only in private kilns but also in official kilns. During this period, the dragons are treated less as a symbol of royalty but more as folkish guardian creatures to ward off evil. The mythical creature is grotesque with a disproportionately huge head and bulging eyes. A higher neck and a raised foot are the most noticeable changes in the transformation.

Vessels for Ancestral Rites and Tombs

Deeply rooted in the Confucian idea of filial piety, Korea continuously produced ritual and burial vessels throughout the Joseon period. The governmental ban could not stop the Confucian society from enriching its ancestral rites with blue and white. These could cost a family more than the price of a house. Numerous myeonggi (burial vessels) were made especially for the tombs of the upper class. So were the offering vessels. The latter were typically decorated with characters rather than figural designs to signify the vessel’s usage, such as je (rite) or byeong (bottle), often in a single or double ring.

Using characters to decorate vessels seems to originate from Korea’s long burial traditions to make myoji, a series of burial tablets to record and honor the life of the buried. There are many extant blue and white examples decorated with poems written in conforming lines to the silhouette of the vessels. Society’s keen interest in literary knowledge also seems to nurture the style.

Stationery for Scholarly Enjoyment

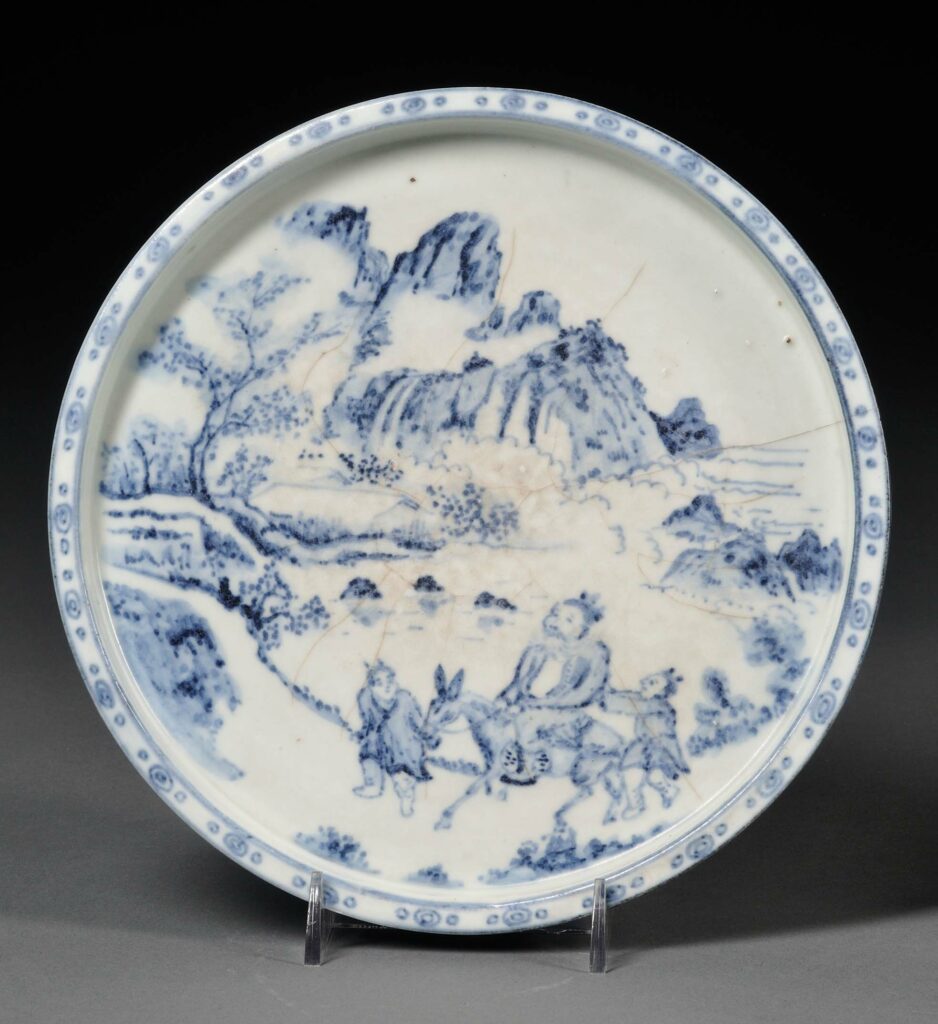

This category includes all manner of writing essentials made for use and aesthetic appreciation. From the 18th century onwards in Korea, large quantities of wine bottles, water droppers, and such were made in various forms. In this type of blue and white, traditional painting subjects are rendered loosely and calligraphically much in the way the artist of the period would brush ink onto paper (Pic 6). Here, the densely patterned bands and multi-tier design scheme of Chinese blue and white that might frame the main image are simplified, reduced to a line, or entirely omitted to allow a larger painting area. Blue pigment was only available to skillful court painters. The primary consumers of blue and white were scholar-officials who seemed to have fueled the development of their painterly style and the preference in taste.

This unique style also began to transform toward the 19th century. The subject rendered in paint expanded to encompass not only traditional ones, such as flowers, plants, and landscapes but also the themes more reflective of the period’s new interest in unusual shapes and patterns as well shown in this four-sided vase decorated with patterns only.

Sold for $3,437

Everyday Vessels for the People

In the early 19th century, when the ban on the production of blue and white was no longer in effect—mainly due to the steady supply of imported blue and the availability of local alternatives—there was an explosive demand for blue and white. The century saw a dramatic transformation and diversification of Korean blue and white in forms, designs, and techniques. Almost all examples of everyday wares and stationery items were decorated in blue with all types of auspicious symbols. Even the ritual vessels with a single character je (rite) in blue changed to include other characters signifying everyday needs and wishes, such as su (longevity) bok, (fortune), gang (health), nyeong (safety), bu (wealth), and hui (happiness). The vessels for high society were no exception. New shapes, methods, and geometric patterns of foreign origin began to embellish Korean blue and white using newly learned application techniques.

Sold for $1,304

Sold for $3,198

Sadly, with the leading official kiln system no longer in operation, the unique charm of Korean blue and white slowly disappeared as mass production increased toward the late 19th century. The white porcelain body became impure, giving it a bluish tint. Draftsmanship deteriorated, often completed by untrained hands with unchecked design schemes. The unique simplicity and the poetic quality of the Korean blue and white gave way to the more robust and livelier styles, dense patterns, and unusual forms found in the masses of imported blue and white from China and Japan.

Collecting Korean Blue and White

Korea’s blue and white is porcelain. It means that the white glaze should be even and glassy smooth regardless of the tint. This feature makes Korean blue and white different from examples made in Southeast Asia or West Asia, which used white slip (liquid clay) to make their pottery pieces white before applying the blue. Watch for the whiteness and clay purity. A snow white or milky white glaze is preferred to bluish-white. It also indirectly suggests that the general quality is controlled by the court officials and is thus superior.

Korean potters used grains of sand or tiny sandy balls to support their white porcelain in the kiln. Look for this type of spur marks around the foot rim or base. Often in dishes, the spur marks appear in the well. In general, the finer the sand, the better the quality.

The unique charm of Korean blue and white lies in the painterly style, usually laid out in delicate free-flowing brushstrokes rendered against a blank white ground. Focus on these types when collecting, as this is characteristic of the most sophisticated specimens.

Find the poetic quality once you have found all of the above qualities in a piece you are considering for purchase. Try to imagine a shy scholar, who likes to travel to far mountains (preferably with waterfalls), enjoys associating the scenery with classic poems and loves to sit on a rock and drink wine contained in a blue and white bottle. If you think that the scholar would like the piece, it is quality.

[1] Korea published many series of books to regulate events at the court during the Joseon period. This particular book of protocol and etiquette was published in 1454 as an appendix to Sejong Silrok (The Veritable Records of King Sejong). Organized in five types of events in eight volumes, the encyclopedic book describes in detail about the participants, equipment, and items in need, venue and time, and procedures and steps, with some illustrations, charts, and graphics.

Consider reading:

Byeongpung | Korean Folding Screens