What Is It?

Simply put, a catalogue raisonné is a compendium of all known works created by an artist. They are the go-to source for a comprehensive understanding of an artist’s oeuvre. The primary focus is to establish a published record of each work: title, approximate year of creation, medium, signature and inscriptions, labels, provenance (or history of ownership), and other information. Perhaps most importantly, a catalogue raisonné assigns a permanent reference number to each known work. As a result, scholars, researchers, and connoisseurs can trace the evolution of artists, their preferences, periods, subjects, and materials. It’s the ultimate records book.

Why is it needed?

In an auction setting, a catalogue raisonné establishes the authenticity of a given work and can lead us to additional information on provenance, exhibition history, literature, and more. Some catalogues raisonnés even list known fakes and key identifying features of inauthentic works, such as Salvador Dali’s print catalogues raisonnés (there are several), lists paper and image sizes, as well as dry stamps of fake works. This information is invaluable in an auction setting – we measure to the millimeter, check the paper and dry stamps of prints, and examine all cataloged works with a fine-tooth comb. In a market ripe with authentic and inauthentic works, these catalogues are priceless works of scholarship.

Who Makes It?

Catalogues raisonnés are compiled by independent scholars, artist foundations, present and former curators, museums, universities, and other institutions devoted to an artist or a movement. The individuals responsible for its compilation have extensive research, scholarship, and exposure to a specific artist. Primarily, they rely on their expertise as connoisseurs to identify the hand of the artist. In some instances though, artists have been involved in the creation of their own catalogue. Our Contemporary Specialist, Kathleen Leland, has a particular favorite entry in John Baldassari’s multi-volume collection, as he was able to contribute to it before his passing in January. A living artist’s involvement in their catalogue raisonné is ideal – so many questions can be answered that otherwise would be impossible to know, the most pressing being “Did you make this?” A living artist’s involvement can cut down on research that could otherwise take years to assemble.

Who Has One?

Most of the big names have catalogues; Manet, Monet, Matisse, Pollock, Picasso, the list goes on and on. Generally, well-known artists with large bodies of scholarship have catalogues raisonné, but that doesn’t mean they are relegated to the elites alone. Where there’s a dedicated scholar, there can be a catalogue. In addition, just because an artist is a major figure in art history doesn’t mean they have a complete published catalogue raisonné or one at all; in many cases, only part of an artist’s output has been catalogued. Andy Warhol’s paintings, sculptures, and drawings have only been catalogued from 1961-1978 – we’re still waiting for paintings from 1978-80 and beyond, though we do have a full prints catalogue (there’s no talk of a photography catalogue). Even Frida Kahlo’s complete works are only published with the full text in German. Catalogues can be organized by time-period, medium, and other variations in one publication or, in many cases, they can be spread out into several volumes that are published over the course of several years. In some cases, an artist may have kept exact records of their works in ledgers or even on the works themselves. I’ve always thought Frank Weston Benson’s catalogue (Paff, 1917) must have been a treat to produce since his prints typically include a signature, an edition number, and the state of the plate.

If you’re unsure as to whether an artist has a catalogue raisonné, try consulting the International Foundation for Art Research (IFAR) website. There is a search tool to see if any artist has a published catalogue or if there’s one being prepared.

Where to find them?

You’re likely not going to buy a catalogue raisonné. Frank Weston Benson’s is $90 new and it’s also out of print, as many are, so that drives up the price, but if you’re a real Benson buff, it could be a unique investment. If you’re looking into the high rollers, you’re going to need to shell out some money; take Jackson Pollock’s for instance, which is nearly $1,000 – it’s four volumes and covers drawings, paintings, prints, sculpture, and other works. Some are just downright obscure—here’s looking at you Robert Mapplethorpe—whose catalogue raisonné exists on a limited number of CDs compatible for Windows only (and I’m scared to imagine what year’s OS you need to access it).

Luckily, catalogues raisonné can often be found in major public libraries and art libraries. Some can be needles in haystacks so it’s best to consult WorldCat.org when trying to pin one down. One should note, however, that WorldCat can’t search every catalog, so you may need to do a little sleuthing through other library catalogs if you’re not seeing a particular spot show up. If you’re interested in looking through a catalogue raisonné at a specific library it’s good to know if there are special requirements necessary to access the books: an appointment, library card, and prior communication with staff informing them of the reason for your research, and so on.

Online

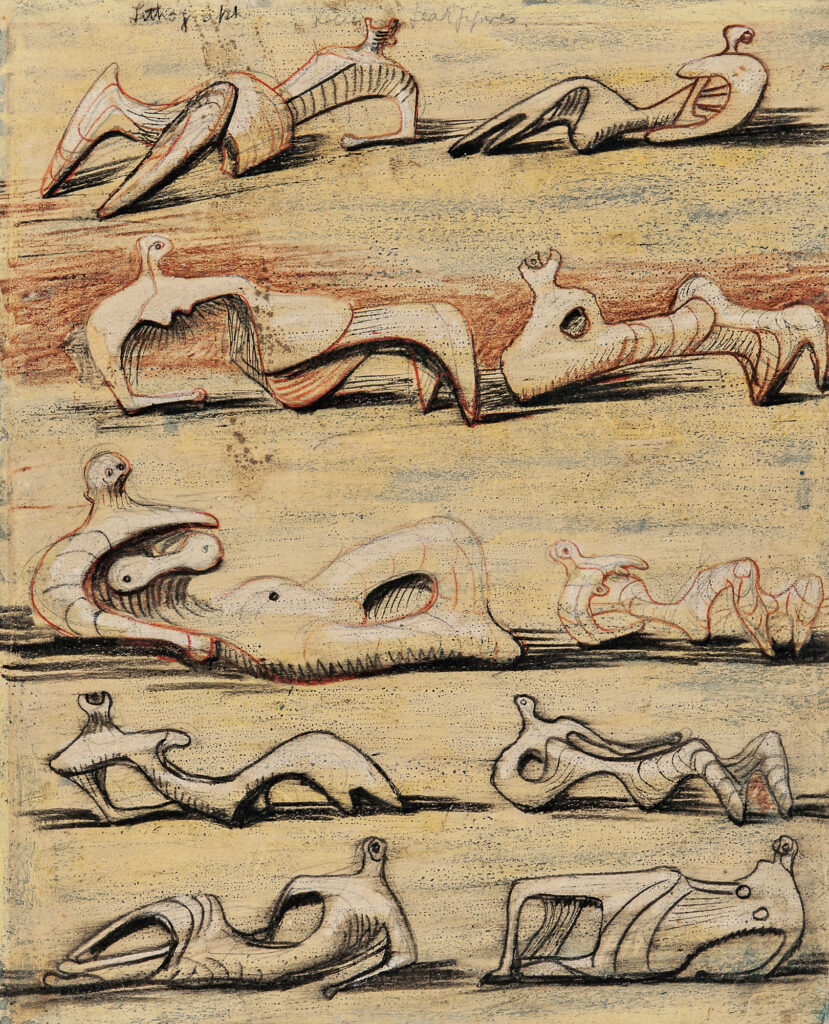

In today’s digital age, some catalogues raisonné are moving online and it’s no wonder why. Online versions can be continuously updated with new works, new owners, and other previously unpublished information. Take for instance Henry Moore’s catalogues—while they’ve been published in print, the artist’s foundation is working to digitize the multi-volume catalogues, which had previously been broken up into drawings, graphic works, and sculpture between three separate editors. This republication of his catalogues in a digital format will include several previously unpublished works. Currently, you can access the artist’s entire output up until 1969.

While Moore’s is free to access, some are a hybrid of free and subscription access, like Sam Francis’ catalogue. With Francis, you can view the full listing of the catalogue with images and dates all for free. However, to access exhibition history, archive numbers, publications, and other information you have to purchase a subscription with an annual fee of $100. Convenient if you’re just a curious person, but slightly inconvenient if you’re trying to establish the authenticity of a work, say, to sell at auction.

Online catalogues also have a bigger advantage when it comes to photos. Instead of being stuck with a thumbnail image, multiple images can be included, and, given the resolution of the photos, you can zoom in! Every brushstroke, every mark made by a burin, all on your computer screen to look at as long as you want. And with the years or sometimes decades it can take to compile a catalogue raisonné, after it finally goes to print there are always new (uncatalogued) works that come out of the woodwork, thus an appendix volume(s) become an inherent necessity. Instead of having to consult one book and then the appendix volume (not to mention having to wait for the appendix to be published), the online catalogue can be updated within a day.

Old vs. New

The University of Glasgow’s Whistler catalogue is also a great illustration of the power of an online format. However, this isn’t to say that Whistler’s previous catalogue raisonné by Edward G. Kennedy, and all of the catalogues raisonnés that came before their digital brethren, are obsolete. In the case of Kennedy’s Whistler catalogue, it is still very much respected, but it does have inconsistencies with the new Glasgow catalogue. There are several works formally attributed to Whistler by Kennedy that do not appear in Glasgow’s catalogue, as the Glasgow catalogue has ruled them misattributions. Wrongly identified works, such as Trixie (Mrs. Beatrice Whistler 470) (formerly Mrs. Whibley in Kennedy’s) have also been retitled in the online version. Another instance of old vs. new would be George Inness’ two catalogues raisonnés, one by Leroy Ireland published in 1965, and the most recent authored by Michael Quick in 2007. Ireland’s edition included 1,541 authentic works by Inness, while Quick refined the number to 1,154 works – within this differential, Quick overturned works Inness had previously deemed authentic. Different times, different scholars, different opinions. Because that’s what it comes down to at the end of the day. Human error is possible. While scholars devote a large portion of their career to learning the ins and outs and fingerprints of one artist, ultimately, it comes down to the eye and the opinion of the current scholar. It can make a muck of the art market – who do you trust? While we are art experts, we wouldn’t begin to assume we know one artist so intimately as to green light a work the leading scholar refutes. Best wait until the next scholar comes along.

New catalogues can also be better for the sheer uptick in quality. Never would I wish someone to go through the Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot catalogue raisonné with its small black and white photos as you look at scene after scene of trees, trying desperately to locate your scene of trees. In these instances, we generally print out black and white copies of the work consigned with us so we have a closer sense of how it would appear in the catalogue. While the new supplements of the Corot catalogue offer bigger pictures, they’re still in black and white. I like to imagine a world one day with an online Corot catalogue.

In old versus new, some scholars will be more thorough, such as the three Picasso catalogues raisonnés compiled by Bloch, Geisser, and Cramer, respectively. As the first published catalogue on Picasso, Bloch’s work was a spectacular resource, listing exact dimensions of prints and covering virtually all of them. Downsides to Bloch were the thumbnail-sized images and each entry given a single page with only ten lines of text. These shortcomings were made evident with Geisser’s publication, which saw a proliferation of detail and illustrations, but its drawbacks are the limited media and dates and the fact that it’s only published in French. The latest in Picasso catalogues is Cramer’s perspective. He covers only those prints which Picasso made for book illustrations, thus he describes the previously overlooked collation of the prints.

The new catalogue raisonné doesn’t dismiss the old; it adds and subtracts, but most importantly it builds off the previous scholarship. Old isn’t void; its expanded. It’s also important to remember, with both old and new, misprints and errors happen. From experience we know two separate works can have a single image duplicated, leaving our work without an image and without a positive catalogue identification, measurements get flipped around from height and width and vice versa, and a slip of the finger can change a year date. Each incoming scholar will add more knowledge and refine what was left behind, and that’s a beautiful thing.

Consider Reading : 3 Ways to Research Book Values Online

Thank you for this informative post! I am doing on-going research for a CR for a little known artist with whom I have connections. This article gives me some good information about what I should do once I get the research to the point I’m comfortable publishing it. I have a couple which I am using as a guideline. Helpful information is very much appreciated! Stay safe Brianna